Why Thousands of CABG Patients Miss Life-Extending Afib Treatment Every Year – and How Surgeons Can Change That

The 49% All-Cause Death Rate Nobody Talks About14

Only 1 in 10 CABG/AVR Patients with Afib Get Surgical Ablation (their best chance to restore sinus rhythm).

What does that look like?

Every year, approximately 161,000 Americans undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery to restore blood flow to blocked coronary arteries.1 These operations can bring a new hope to these patients—a chance to relieve chest pain, prevent heart attacks, and extend life.

But there's a critical gap between the potential to improve quality of life and survival, and what actually happens in a large number operating rooms across America.

The reality: 20% of CABG patients have atrial fibrillation (Afib),2 however a large majority leave the operating room (OR) with their rhythm disorder undiagnosed or ignored.

That means approximately 32,200 patients could benefit from concomitant Afib treatment each year.

Despite clear guideline recommendations and mounting evidence, surgical Afib ablation during CABG remains the exception rather than the rule, resulting in the disappointing treatment rates we see today.

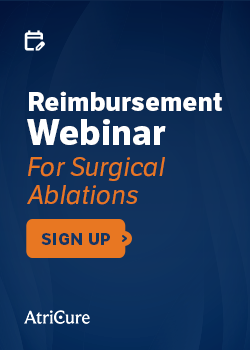

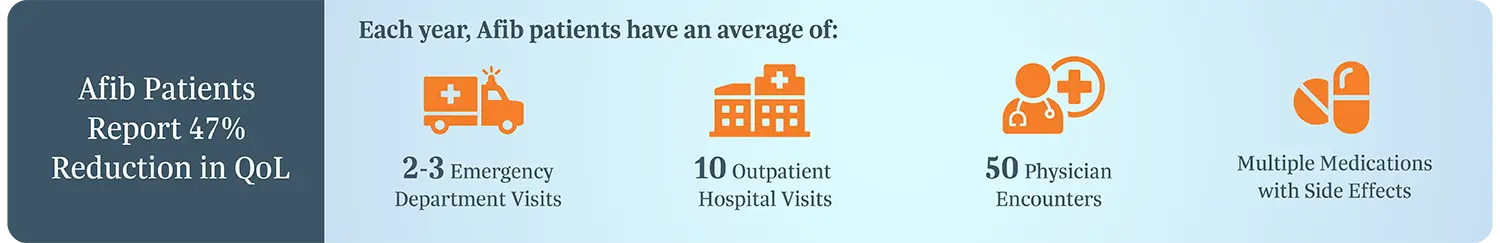

What it Means for Patients Leaving the OR With Afib

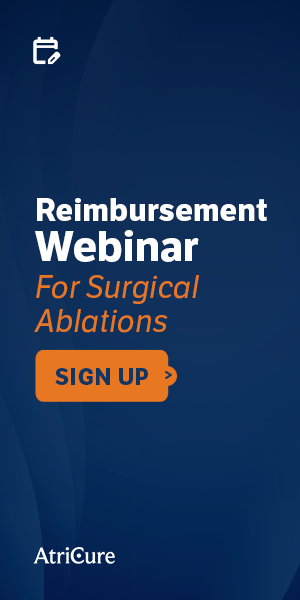

Patients diagnosed with Afib have a lower 5-year survival than the most-feared cancers.14

*Image 1

The consequences of leaving Afib untreated extend beyond the immediate surgical success from revascularization. Patients with untreated Afib have a 64% increased likelihood of experiencing early mortality following CABG.3 Adding to that, untreated Afib leads to a 2.8x increase in late cardiac death.4

In addition to reduced long-term survival, when surgeons choose not to treat Afib during CABG, they're not just missing a procedural opportunity—they're potentially leaving their patients with these challenges because Afib only gets worse:

- Progressive rhythm deterioration that becomes harder to treat over time

- Increased stroke risk that persists despite successful coronary revascularization

- Heart failure progression which undermines the benefits of bypass surgery, and is the leading cause of death in Afib patients.16

*Image 2

*Image 2

The Evidence Evolution: What's Changed?

The landscape of evidence supporting concomitant Afib treatment has experienced dramatic improvement. Contemporary high-quality studies have brought a fresh perspective to challenge old assumptions and add more clarity, demonstrating that surgical ablation not only improves long-term survival, but is safe and effective:

Safety Questions Addressed

- No significant difference in 30-day mortality between CABG alone vs. CABG + ablation5

- No unadjusted differences in perioperative complications, including renal failure, stroke, bleeding, or death6

- Modern techniques pose minimal additional risk while providing substantial long-term benefit4,5

Proven Efficacy

- Stroke readmissions reduced by 50% with left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) or LAAO + surgical ablation6

- Surgical ablation is comparable in value to an extra bypass graft in terms of survival benefit4

- Long-term survival rates improved with comprehensive Afib treatment8

Operational Efficiency and Reduced Complexity

- Streamlined approaches focus on essential lesion sets4,9 enabling surgeons to tailor the surgical ablation to each individual patient.

- Innovative technology enables effective ablation without opening the atrium9,10 and can be done in less than 10 minutes.

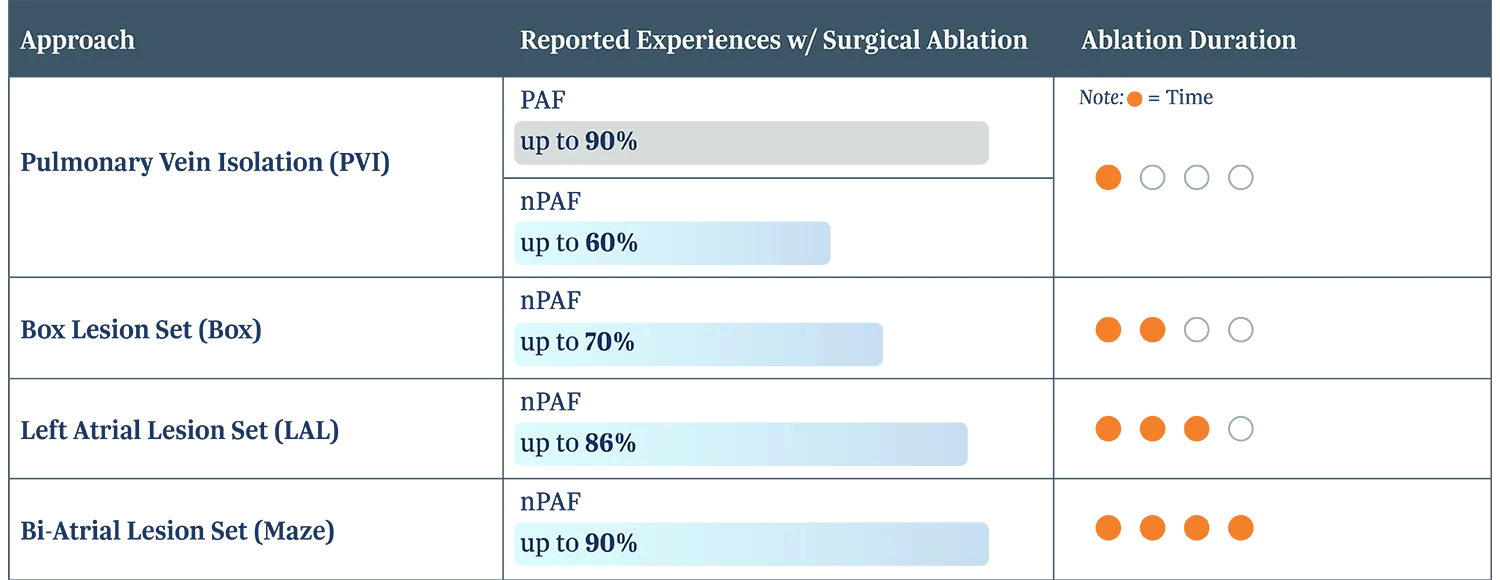

Cox-Maze IV is the most efficacious treatment for Afib, but even a partial Cox-Maze can restore sinus rhythm.

*Image 3

*Image 3

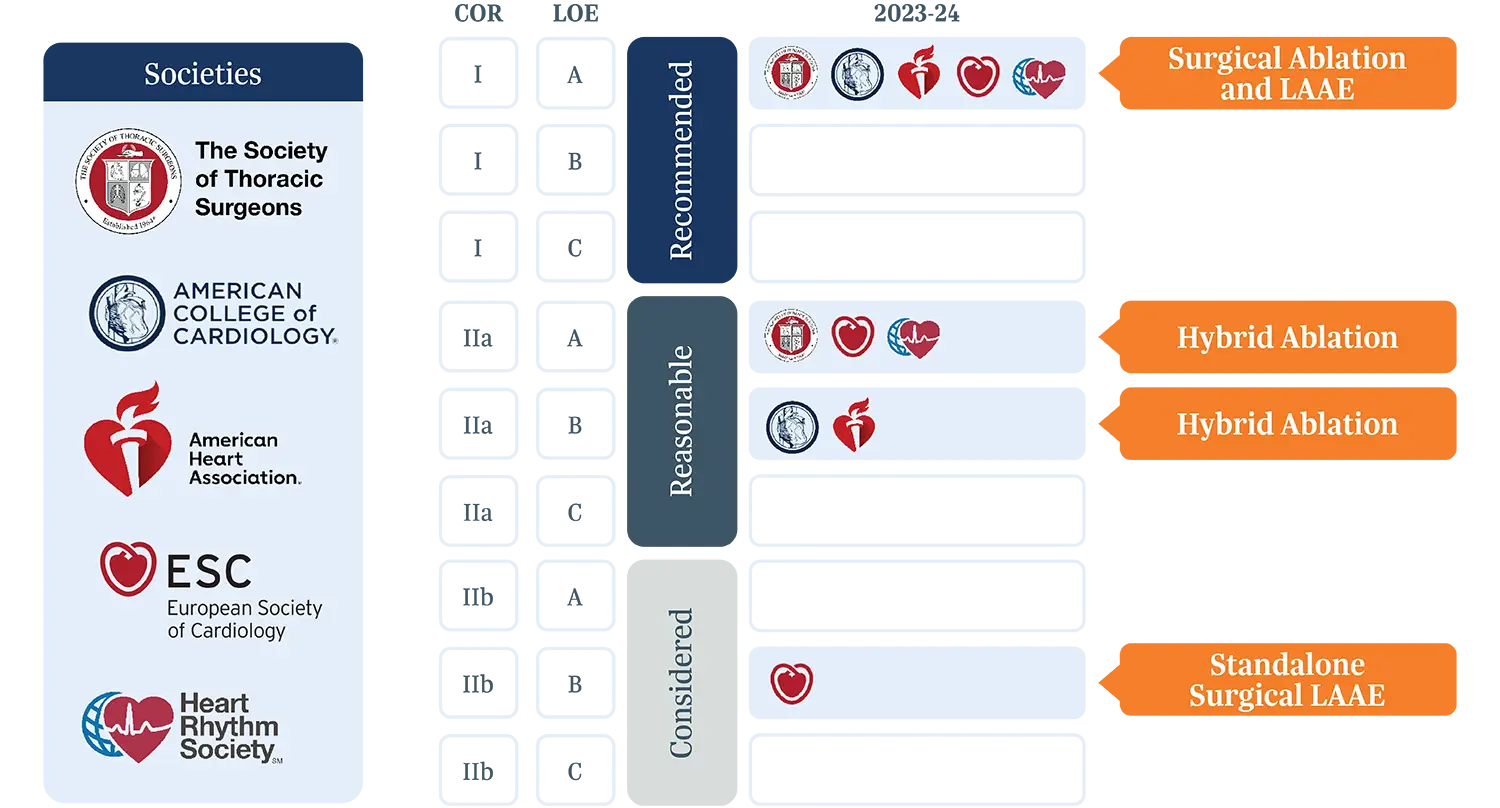

Advancing Guidelines

The ambiguity from the past that led to some uncertainty in clinical decision-making has also seen significant improvement:

2023 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Guidelines

- Class I recommendation: Surgical ablation for Afib is RECOMMENDED for any first-time nonemergent concomitant non-mitral operation11

- Class IA recommendation: LAA obliteration for Afib is RECOMMENDED for all first-time nonemergent cardiac surgery procedures11

2024 EHRA/HRS/APHRS/LAHRS Expert Consensus

- Advice TO DO: Bi-atrial Cox-Maze procedure or a minimum of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) plus left atrial posterior wall isolation is beneficial in patients undergoing surgical Afib ablation concomitant to left atrial open cardiac surgery.12

*Image 4

Financial Considerations:

There’s positive momentum on the economic side, as well. Reimbursement pathways are well-established with specific DRG codes, and recent reimbursement increases for CABG adding surgical ablation.13 And, hospitals and systems can benefit from the cost savings through reduced readmissions and stroke prevention.

Looking Ahead: Restoring Sinus Rhythm Should be the Standard of Care

Afib doesn’t wait. And it doesn’t stop. It’s a progressive disease and only intervention can halt the disease or potentially cure it.

Afib patients undergoing non-atriotomy surgery such as CABG are 5x less likely to get guidelines recommended treatment – but, there’s been a paradigm shift to treat Afib more aggressively and sooner, before it progresses or exacerbates other comorbidities.

Mounting evidence has cleared up questions from the past, the guidelines are supportive, and recent technology has unlocked new possibilities.

The next step towards treating Afib with the seriousness it deserves is a fundamental shift in the approach to Afib in CABG surgery—from viewing sinus rhythm restoration as optional to recognizing it as essential.

All the recent momentum has shifted the question from whether to treat Afib during CABG, but whether not treating it can be justified. Performing surgical ablation is just as important as revascularization.4 Because patients deserve to be normal – in sinus rhythm.